Uh, are the ketamine startups OK?

Plus: TikTok’s newest mental health trend, beauty’s wellness bet, the unexpected group hacking wearables, and more industry news.

Well To Do is nearing 14,000 subscribers! This newsletter started back in 2017, back when I covered the wellness industry for Fast Company, and I’d love to keep it going. If you enjoy this newsletter, do consider a full subscription!

The ketamine clinic boom and bust

“I would say it's very much for the average person,” Ronan Levy, CEO of psychedelic wellness startup Field Trip, told me of ketamine-assisted therapy during an interview earlier this year. Psychedelics could help the quarter of Americans dealing with a mental health challenge, he explained. They could, for example, help those with high anxiety, he said, adding that the results his clinics generated were “fantastic.”

Field Trip, one of the largest providers of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in the U.S., raised CA$100 million from investors. It went public on the Canadian Securities Exchange and planned to open 75 luxe spa-esque clinics by the end of next year. Field Trip was hailed as the future of psychedelics, poised to usher in a new era of revolutionary treatment for depression, PTSD, and more. It was the cool kid leader in the $800 million U.S. ketamine market.

But by April, Field Trip had closed five of its nine clinics. Around the same time, Ketamine Wellness Centers, which operated 13 clinics in nine states, abruptly shut down. Revitalist Lifestyle & Wellness, a chain of ketamine clinics, failed to make interest payments on its debt last month. These closures follow Actify Neurotherapies, which permanently closed its dozen clinics.

Meanwhile, the greater psychedelics industry has witnessed similar challenges: In March, psychedelic retreat and practitioner training provider Synthesis Institute filed for bankruptcy. Bloomberg reports an index of stocks down more than 80% from its peak in 2021. (Note: Ketamine is not technically classified as a psychedelic, but does have psychedelic effects.)

Seemingly overnight, these highly-publicized venture-backed businesses went kaput. Patients, with little advance notice, scrambled for ongoing treatment. Employees felt blindsided. And ketamine specialists-in-training are now navigating a far more complicated career path than they had anticipated. “My good friend just did her training for ketamine therapy,” a friend recently DM’ed me. “They trained all these people and then realized there's not enough clientele yet.”

So what exactly is going on in the ketamine space, once heralded as the next big wellness boom—“the next cannabis”?

To start, ketamine clinics always faced an uphill battle: single treatments ranged between $350 to $900 and were rarely covered by insurance since ketamine has not yet been approved for the treatment of mental health disorders. (The drug has been FDA approved for off-label use to treat a variety of mental health issues). Many clinics pushed at least six sessions for results, topping several thousand dollars. That meant only a small slice of the population could afford such a service, and increasingly, the competition included new, more affordable at-home telehealth services such as Mindbloom (which hovers around $100-$200).

The general public, meanwhile, isn’t educated enough on what ketamine offers or how it precisely works; there’s a whole lot of mystery, compounded by media reports that still debate the emerging science. People might sooner try ketamine once out of curiosity, but still balk at committing to a pricey treatment program. I know plenty of people who signed up for a session simply because they read so much about ketamine, but never took it seriously. To them, it was just another wellness novelty, no different than cupping, an ayahuasca retreat, or cryotherapy. That these clinics looked like spas certainly solidified its recreational rebrand (although ask anyone who’s tried it and they’ll tell you it’s far from a massage).

Then, of course, there’s the issue of private equity in a nascent sector still pursuing legitimacy. With so much hype, investors likely overestimated the demand for a drug still lacking healthcare’s blessing as a mental health treatment. An aggressive growth strategy backfired, especially since it’s unclear whether ketamine lends itself to the current clinic model these companies adopted. Scaling seems tricky at best.

Not to mention, does rapid growth belong in such an emerging field? Inevitably, investor pressures lead to debatable business decisions.

One of the concerns experts reiterated to me while I was reporting on Field Trip for my LA Times feature on “social wellness” was that in the rush to capitalize on ketamine (and maximize profits), treatment wasn’t necessarily folded into proper comprehensive care—thorough patient screening, mental health professional staffing, or as part of a bigger treatment plan in coordination with healthcare providers. An investigation by STAT found that many clinics weren’t abiding by the American Psychiatric Association’s recommendations, all while inflating potential promises and downplaying risks in marketing.

It also isn’t clear how much of the positive effects are due to ketamine versus the talk therapy that often follows it. As such, experts worry about clients being rushed through treatment or opting for the at-home model (which might mean skipping the psychotherapy part and/or without professional supervision).

Gerard Sanacora, MD, Ph.D., a notable scientist in ketamine research, notes that this is not a treatment to be given in isolation: “All of the studies presented for consideration of FDA-approval were done with very close psychiatric follow-up. It is incredibly naïve and uninformed to think ketamine alone will make your depression go away. It’s a part of a treatment plan, not the treatment plan.”

STAT News reports that Field Trip was under pressure as money was running out, thereby propelling the startup to explore an at-home service despite concerns:

It was a challenging assignment, figuring out how to safely provide a sedative to depressed patients away from clinic supervision, but [VP of clinical services] Elizabeth Wolfson said senior leaders gave her just a week or two, telling her to “hurry up and do it.”

In the end, the new offering lasted barely a month before executives decided it wasn’t lucrative enough and added it to the pile of scrapped initiatives.

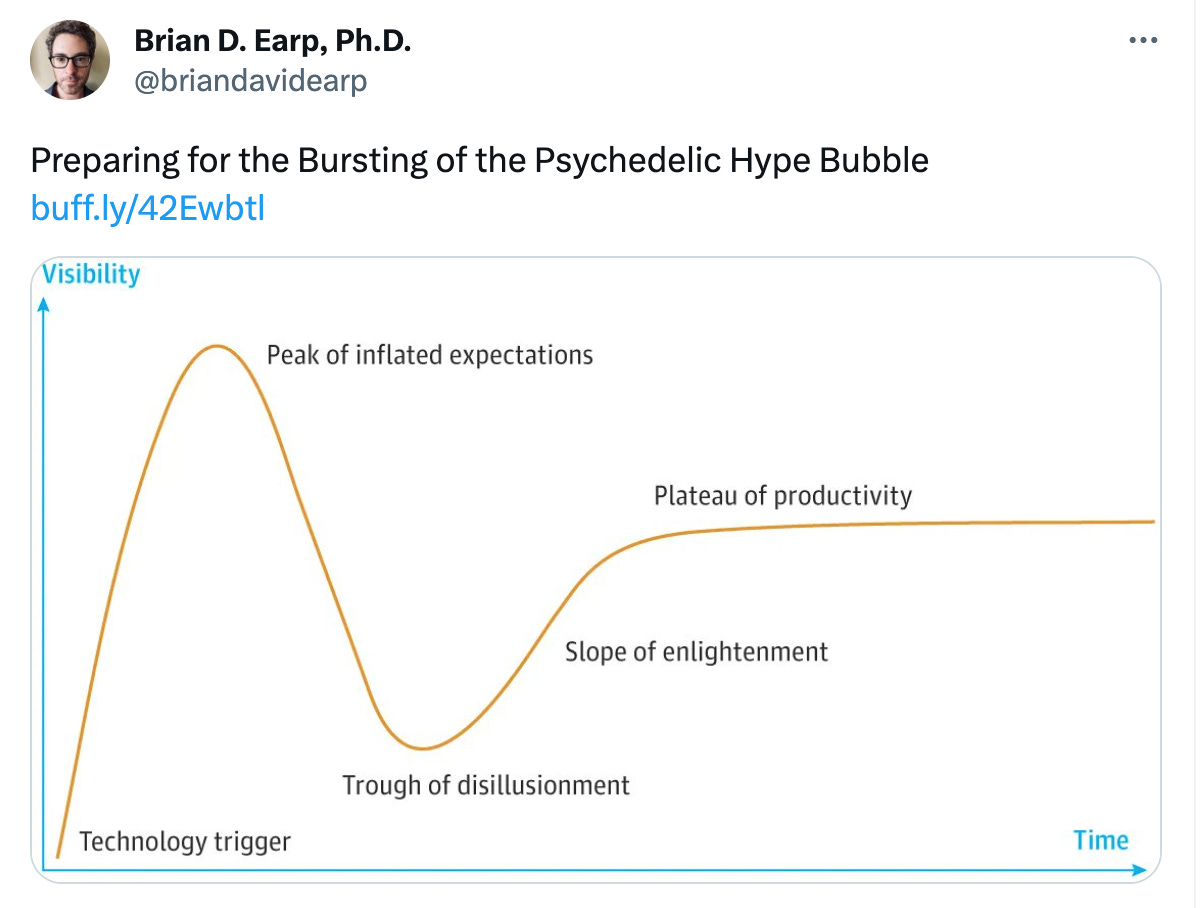

Psychedelics show promise in therapeutic treatment, but research is still in its infancy. Currently, we’re caught between overhyped cure-all claims and the incoming bashing of psychedelics—the boom and bust of trend coverage—or as David B. Yaden, Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research describes it, the extreme between “superenthusiasists” and “superskeptics.”

“Psychedelic research is fascinating and exciting and there’s reason to be hopeful,” Jonathan N. Stea, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist (who runs the Mind the Science newsletter), told me during an interview a few months back. “But this perspective needs to be balanced against the temptation of premature adoption in particular treatment plans and the reality of potential harm and unintended consequences, such as side effects, the promotion of self-medicating, and the determent of more established, evidence-based treatments.”

Bottom line: The research that does exist is mixed and, at times, flawed. But it is improving.

Some worry we’re at risk of “overcorrecting,” pushing back research to a more cautious climate that could halt scientific progress (like in the 1960s). Others say ketamine is in no way “over” nor will research institutions likely abandon their efforts. There are over 30 publicly traded companies researching or developing psychedelics for medical or therapeutic use. Drug conglomerates are still in the game, with Johnson & Johnson pursuing recent studies for its ketamine-derived nasal spray. Overall, when it comes to ketamine clinics, it could very well be that they were a bit too early—perhaps by a decade—and too ambitious in their scaling efforts. Many, of course, simply succumb to hiccups in any emerging field still trying to find its footing with the public.

Ketamine's Woo-Woo Rebrand: What's at stake when ketamine is marketed as wellness? I share a few of my thoughts. (Harper’s Bazaar)

The Psychedelic Startup Uniquely Focused on Women’s Health: “When we look at the drugs on the market … they've been designed for men.” (Well To Do)

Scientists Gave People Psychedelics—and Then Erased Their Memory: How do you fit psychedelics into a study design that seems unable to contain it? (Wired)

A Gym for Your Feelings? Emotional Support Now Comes with a Membership fee: Social wellness initiatives are catching on in Silicon Valley, the workplace, and unexpected sectors (like psychedelics)—for a price. (LA Times, by your truly)

—Rina Raphael, author of The Gospel of Wellness

News & Trends:

Lord Jones shuts down, latest victim of CBD slowdown: The lifestyle brand—once sold in Sephora—follows Kristen Bell’s CBD skincare line Happy Dance, Beboe Therapies, WLDKAT, and more. See also: How the wellness industry is shifting. (Beauty Independent)

Jonah Hill skewers self-help gurus with satirical lifestyle wellness brand: The label has one simple goal: “to spread joy throughout the universe by monetizing happiness.” See also: my thoughts on the “mental health!” industry. (THR)

NYC rolls out health vending machines: Overseen by the Health and Mental Hygiene and Services dept., the machines contain Covid-19 tests, hygiene products, and a number of other health products. (Boro24)

Beauty brands want a bigger piece of the wellness pie: New opportunities include sleep, sexual intimacy, and ingestible beauty. (Glossy)

Meanwhile, why is it so hard for the beauty industry to get wellness right? There’s a lot of excitement and potential, “but nailing the experience hasn’t been easy.” (BoF)

Who can afford America’s perfect neighborhood? Longmont, Colorado is considered a “shining example of a livable, walkable community,” where residents stroll on over to Pilates classes or a European bakery. But with the median home sales price nearly $1 million, it serves as an example of how unaffordable these idyllic communities are. (The Guardian)

Related: Utopic wellness communities are a multi-billion dollar real estate trend and Silicon Valley’s quest to build the wellness community of the future.

Inside Drew Barrymore’s meditation room: The internet has a lot of opinions on this one. (NY mag)

No, Splenda isn’t giving you cancer: Recent headlines about sweeteners are extremely misleading. (Health Nerd)

To Gen Z, food is the new luxury: Luxury brands increasingly incorporate food to appeal to foodies and younger health conscious consumers. Expect more Erewhon smoothie collabs, folks. (Vogue Business)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Well To Do to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.